7 More Hospital

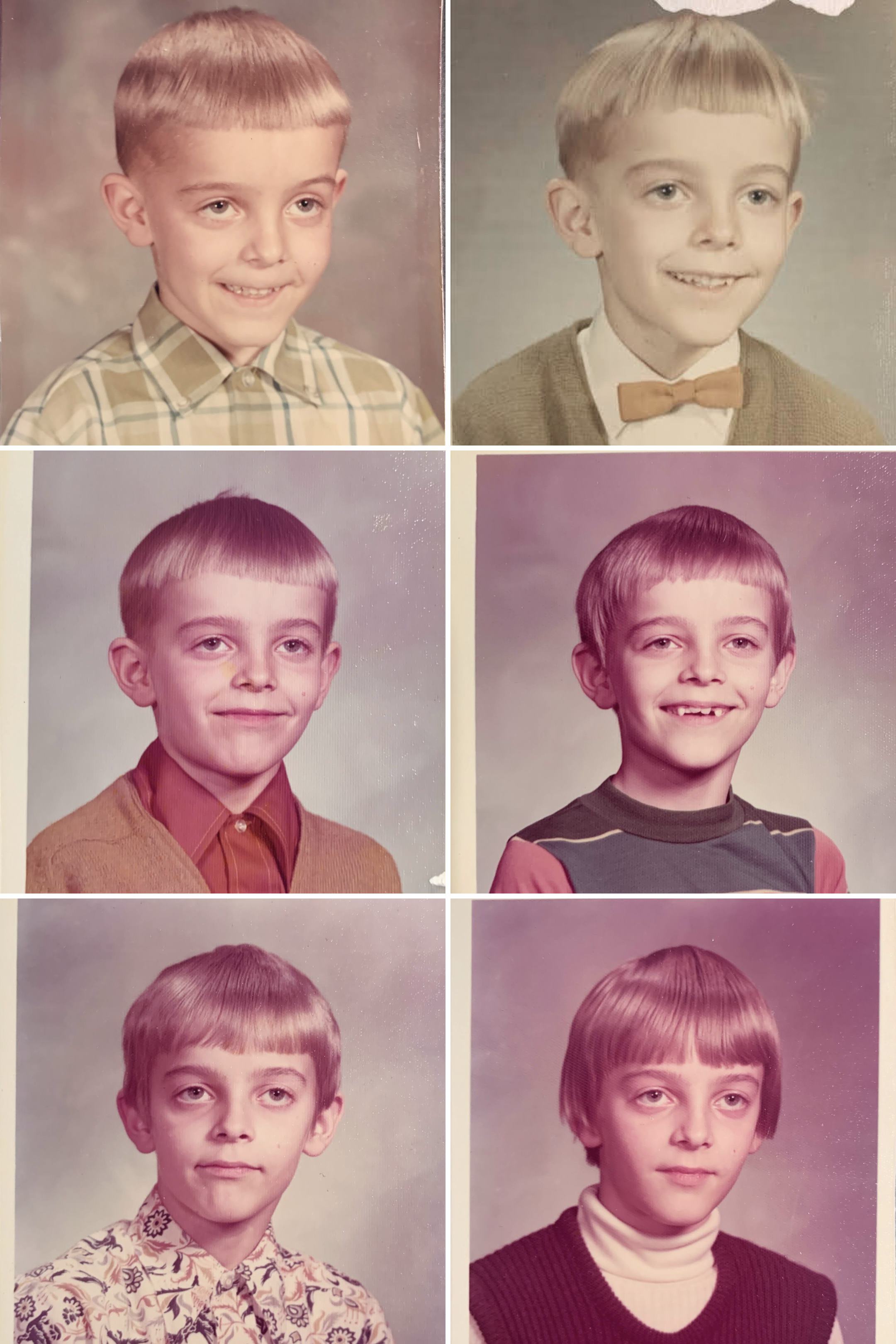

After kindergarten, after my appendix had been removed, I seemed to have fully recovered, yet I continued to have stomach pains, which my mother treated with Pepto Bismol. The raw pink taste of the gallons I drank still hasn’t faded after all these years, but at the time my situation didn’t seem particularly disturbing. After all, I was a small boy who’d just had major surgery. Otherwise I continued to develop normally and all seemed fine.

But sometime in third grade, my situation became much worse. The doctors wrote the following notes on August 14, 1971:

The child had been sick for about a year and probably more. He would chronic abdominal pain and off and on his breathing was not regular. There was something wrong going on in his abdomen and the parents did not have any insurance, his father is a minister and does not have much money and he did not bring the child for exam. On admission he was chronically ill and he was in a mal-nutritive state. He was slightly toxic and his growth was a little below the average. For the past three or four months the child would not eat because he stated to his parents that his abdomen gets tight when he eats and at times while he is eating he would stop eating because of the same pain. This has been going on chronically for the past three or four months and prior to admission his symptoms became worse and the day of admission increased in intensity and he became acutely ill.

Unlike kindergarten, where I distinctly remember the day I went home early from school due to illness, I have no memory of how or why I ended up in the hospital this time. Looking back at the doctor’s notes now, after all these years, I see that my situation was far more serious than my younger self could comprehend. The small town doctors in Neillsville gave up on me. Unable to help further, they loaded me into an ambulance and transported me to the much bigger hospital thirty miles away in Marshfield.

I was assigned to a Japanese-American doctor named Dr. Toyama. Years later, as an adult who had spent years living in Japan, I went back to Marshfield and found him again. I learned he was an issei—his parents had come to the US before he was born, and he grew up here (I don’t remember where exactly). Somehow he ended up living in the middle of Wisconsin and had spent his entire career there. He didn’t remember me very well – he claims he did, but with so many thousands of patients over the years it’s hard to tell exactly – but when I was a suffering eight year old, he was the center of my existence.

Upon arrival at Marshfield, Dr. Toyoma wrote in his notes about me:

He was doubled up in fetal position…the abdomen was flat, colostomy on the left side which was not yet matured…bowel sounds were absent…The child did appear exhausted.

Due to the pain, Dr. Toyama didn’t do long tube intubation and went straight to surgery, where

he was found to have a tight adhesive obstruction in several areas with collapsed bowel distal to the obstruction. The obstruction was in the mid small bowel. There was purulent non-foul fluid in the peritoneal cavity at the time of exploration, however, no perforation was noted. The colon appeared normal…cultures of the peritoneal fluid grew out pure culture of E-coli.

After conferring with the Neillsville doctors and my parents, Dr. Toyama decided that my original surgery hadn’t addressed the real problem, which was a sigmoid volvulus, an intestine that was predisposed to become wrapped around itself and become blocked. I had been sick for quite a while and there was a significant danger I had already sustained permanent damage, he feared, so I would require a series of surgeries to uncover the underlying problem and find a permanent solution.

Meanwhile, my current situation was extremely serious, he warned. I was so weak that there was already a good chance I wouldn’t survive. My brother and sister were called to the hospital – normally young children weren’t allowed inside the patient area – and were told, gently, that this might be the last time they see me.

I knew I was not well, but at the same time I also knew that I was very special: a constant stream of friends, relatives, and neighbors came to my bedside bringing all manner of presents. I was the center of attention! If anyone told me there was a chance I’d never leave the hospital, I don’t remember it, because I certainly didn’t feel like my life might soon be ending.

In fact, among other memories of that time, I remember thinking how wonderful it would be to fly in an airplane, maybe even become an airline pilot. I don’t think I was particularly worried one way or another about the future.

Marshfield was a great, modern hospital, with its own pediatric ward, full of other children, extra-friendly nurses and even special activities and visitors. Famous visitors who passed through town would often stop to see the hospital, and of course the pediatric ward was a must-see for them. One day the famous basketball performance team, Harlem Globetrotters, came in to my bedside and signed autographs for me. Lying in bed with an IV, tubes coming out of my nose, and with my weak, skinny arms, I must have been a pathetic sight, but I never remember any sense of concern around me. To me, it was all a place of wonder and nonstop attention.

There was one exception to my sense of calm. Since Neillsville was about thirty miles away, my parents – usually my mother – had to drive quite a distance to see me. Since she was responsible for my siblings as well, who were in school but still needed to be fed and cared for, she could be with me only during the day. The evenings after she left, and especially the mornings before she arrived were difficult and lonely.

My religion was a big influence on everything I did, so naturally I saw my hospitalization in the context of God and His purpose for my still short life. I had been taught that only a tiny few people had a true understanding of God’s plan for humanity, and that even among those of us who believed, we still fell short of what God wanted. And a sin is a sin; even one tiny, seemingly insignificant breach of God’s rules could keep you out of heaven just as certainly as the most dastardly bank robbery or murder. I knew that I sinned too – sometimes the worst sins of all are those that you do subconsciously, non-deliberately, in a moment of forgetfulness, and I had plenty of those.

Some sins are passive – what I would later learn to call “sins of omission”—when we know that we should do something but we don’t. These are among the most annoying sins because they result from laziness, or lack of willpower, and sometimes from simple shyness. For example, I knew that my fellow hospital patients were mostly unbelievers, and that I owed it to them to share my knowledge of the saving grace of Jesus Christ. By not sharing – by keeping silent when I knew that they could benefit from this message – wasn’t I falling into a terrible trap of the Devil? Wasn’t that a sin?

I knew the importance of keeping up my faith with regular prayer and Bible reading. Sometimes I forgot, or was too lazy or distracted. Wasn’t that too a breach of God’s will – a sin?

Although you’d think that an eight-year-old, weak with sickness, tired and injected with medications, would not have cause to think much of these things, in fact it was at the center of my mind. I knew that God loved me, and that it was only through prayer and diligently following His will that I had survived this sickness at all, but I also knew he was testing me for some greater purpose. Would I pass the test?

One morning, after a particularly difficult night of anxiety over this, I woke up thinking I knew the answer: clearly I had failed the test. I was convinced that this meant I would not be going to heaven at all, and with the imminent Rapture an ever-present possibility, I suddenly had a strong premonition that last night had been the moment when Christ returned to earth, and I was left behind.

I began to cry. A nurse soon noticed this and immediately tried to comfort me.

“What’s wrong?” she asked, holding my hand with a voice of sincere concern.

“I’m afraid,” I said, hesitating. Should I tell her my real fear – that the Rapture had happened last night and that I had missed it? If this were true, then it meant my nurse had missed it as well. Was this really the news that I wanted to break to her at this moment? First I’d need to explain all those other details of the Gospel, and she’d want to ask questions, perhaps challenge me with doubts. This whole explanation could take a long time, and at this moment I was just feeling sad that I wouldn’t see my mother again.

I decided to skip the long explanation and just cut to the point.

“I’m afraid,” I said, continuing, “that my mother won’t be coming back.”

As an adult looking back on this, I can imagine the reaction this produced in the nurse, who no doubt wondered what sort of family life could cause a little boy to doubt that his mother would visit him in the hospital. She was calm about it, though, listening to me and offering her reassurances that my mother would be there the same time she always was.

She was right: my mother walked into the room, to my immediate relief. The nurse explained that I had been especially anxious that morning, worried that my mother wouldn’t return, that this was a normal type of separation anxiety, not to be concerned, etc. That was it.

But I wonder if this had happened today, maybe she would have been required to note my behavior somewhere, perhaps a side report to a doctor or a social worker to be on the lookout for signs of family abuse or some other tragedy.

The burden of caring for me was so time-consuming that around this time my brother and sister were often dropped at the farm of our Pulokas Grandparents. I was too sick to know much about the time they spent there, but I know they enjoyed it. Partly of course it was because their grandmother spoiled them – delicious food and plenty of toys. Life on a farm can be especially fun for little kids. Gary enjoyed looking at the farm equipment – Grandpa even let him drive the tractor. They played in the hay mow of the barn, rearranging stacks of hay to make pretend forts. And of course there were animals: dogs, cats, rabbits and cows. Gary was old enough that occasionally Grandma would let him try milking, though despite Grandma’s patience he showed too little interest to be of much help.

There would be plenty of other visits to Grandma’s house when I came out of the hospital, but I know Gary and Connie kept special memories of that summer’s lengthy visit, when the two of them developed their first tastes of independence away from parents.